Dr Cheah Wui Ling – Bringing International Criminal Law to USP

By Ong Lishan (Industrial and Systems Engineering, Class of 2016)

Lishan is a student writer for USP Highlights.

Published: 16 August 2016

For Assistant Law Professor Dr Cheah Wui Ling (Law, Class of 2003), Law was not her first choice. In fact, she had wanted to be a writer at National Geographic – she was even offered a place at Oxford University to study Geography. Her father, a lawyer, wanted her to study Law as he deemed it a safer option. “He probably wasn’t very happy that I decided to do public international and human rights law,” Dr Cheah joked.

Today, Dr Cheah teaches international criminal law at the NUS Faculty of Law, and in some semesters, USP Singapore Studies module USE2320 Transitional Justice and War Crimes Trials. She previously worked at the Serious Crimes Unit in Timor Leste (2004), and at Interpol’s General Secretariat in Lyon, France (2005-6). In 2011, she was a Visiting Professional at the International Criminal Court. Currently, she is also the Senior Advisor at the Forum for International Criminal and Humanitarian Law at the Centre for International Law Research and Policy in Brussels, Belgium.

Dr Cheah speaking at a book launch event at the 13th Session of the International Criminal Court Assembly of States Parties in New York (UN Headquarters, 12 December 2015). Dr Cheah is co-editor of the Historical Origins of International Criminal Law anthology (4 volumes), which explores the historical, cultural and intellectual origins of international criminal law and its evolution.

Her First Brushes with Public Interest Law

About ten years ago, there were few modules on international and human rights law, but this has changed. “There is now a larger demand from students wanting to explore careers related to public interest and human rights that don’t fall into your typical corporate, contract law, usual mainstream path,” Dr Cheah said.

Back then, a trip to Cambodia as part of the Talent Development Programme, the predecessor of USP, sparked her interest in Law. “Although we were in the same region as the Cambodians whom we met and took classes with, I was shocked at the disparity in resources. We were housed in a five-star hotel, but it was a complete disparity when we visited their homes,” she said. This prompted her to ponder the role of international law in facilitating better resource reallocation. She became more interested in modules which addressed social inequality and human rights.

Another overseas experience – a student exchange at Washington University in St. Louis – gave her real hands-on experience. Then, Dr Cheah took a module that allowed her to work in a civil justice legal clinic that dealt with family law issues.

The hands-on stint during her exchange convinced Dr Cheah that it would be great to have a legal clinic module in Singapore, or at least something similar, where students could have hands-on experience in pro bono work.

Dr Cheah as an exchange student in Washington DC

Helping to Set Up the Innocence Project (Singapore)

“During my time [as an undergraduate], there was no pro bono club. Pro bono work was driven by pro bono lawyers for the longest time who were doing it quietly. People don’t realise how quickly it has grown. It is now mandatory in Law School,” Dr Cheah said.

Dr Cheah considers helping students set up the Innocence Project (Singapore) to be her career’s biggest achievement to-date. The Project is a branch within the NUS Criminal Justice Club and it assesses claims of wrongful convictions. She was approached to be the project’s supervisor by a law student who, like her, had worked at a legal clinic in the US. Students would receive applications from people in prison who believe they have been wrongfully convicted, and these students would make preliminary assessments on the merits of these applications.

Dr Cheah emphasises the Project’s student-driven nature. “Students are empowered to go to prison to interview clients, and decide what kind of court documents they can refer to for leads. They draw up a report either proposing that we look for a pro bono lawyer who can reopen the case, or explaining that it is not a case of wrongful conviction, such as when the applicant is only looking to get his/her sentence reduced.” Supervisors would approve the students’ reports, and only offer guidance such as connecting students with the relevant people.

Although it took a lot of time and resources to establish the groundwork, the Project is extremely meaningful to her. “We don’t have a body that specifically deals with wrongful convictions. Cases are usually taken up at the trial or appeal stages, but rarely after. But evidence revealing wrongful convictions may only appear after many years.”

First of its kind in Singapore, Dr Cheah says that the Project is now well-regarded by the courts, Law Society of Singapore, Attorney-General’s Chambers, and Ministry of Law. Impressed by the Project’s progress so far, she said, “You don’t know how much young people are capable of until they are given the opportunity. It’s not only their energy and enthusiasm, but also their professionalism and attention to detail that they bring to a job which you expect only professionals to be able to do.”

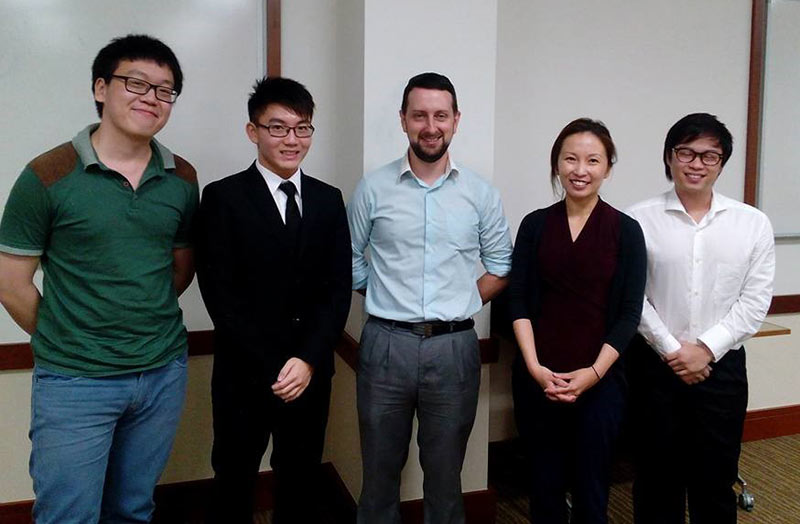

Dr Cheah with student leaders of the Innocence Project (Singapore) and Eoin Ó Muimhneacháin, Assistant Director of the Law Society of Singapore. At a talk on 'Eyewitness Testimony and Wrongful Convictions' at NUS-Yale (30 September 2015).

Transitional Justice and War Crime Trials

Moving beyond NUS Law School, Dr Cheah enjoys teaching and working with USP students. In USP, her module USE2320 Transitional Justice and War Crimes Trials is the only USP module covering international law. Her module explores the range of processes and practices of justice implemented to address instances of mass atrocities committed with state backing. Typically, we fall back on war crime trials, but this module raises non-legal alternatives, such as truth and reconciliation commissions, memorialisation processes, fact-finding commissions, amnesties and apologies.

Why is this module relevant to us as Singaporeans? “We often think that Singapore is so safe and stable. But in Singapore, war crime trials were conducted to address the atrocities conducted by the Japanese military. This is part of our history,” Dr Cheah explained. “There are still atrocities and human needs around us in the region. Singapore is in a good position to play a role in capacity building and humanitarian outreach. We need to conceptualise a larger role for Singapore in the regional and international environment. Even political discourse focuses on national self-interest, rather than our role in the larger public interest.”

While her classes cover cases from other countries such as Rwanda, Cambodia and Bangladesh, the project and paper are Singapore-centred. Aloysius Seah (Industrial and Systems Engineering + USP, Class of 2016) who took the module shared, “In Singapore, war crimes are usually forgotten or not deliberated. This module showed how World War Two crimes were resolved given the political and economic background of the time. The project and paper required us to examine transitional justice as applied to Indian Prisoners-of-War, comfort women and the Sook Ching massacre.”

To Dr Cheah, teaching at USP has been interesting. “USP students are more open to taking their own steps to explore what we discuss in class. The IVLE Forum buzzes throughout the week.” In contrast, she feels that Law students may be less exploratory in their approach to learning. She attributes this to the glut of law students, that they tend to “focus a lot on doing well” to keep up with the competition.

The multidisciplinary profile of a typical USP class is also evident and eye-opening. Dr Cheah gave this example, “Sociology or Psychology students may compare how witnesses may feel testifying before a truth and reconciliation commission, versus in front of a trial.”

As an Engineering student, Aloysius found that he lacked some of the background in socio-political concepts in the module. However, learning about transitional justice as a new concept was worth it. “Punitive justice is usually the legal go-to norm in a properly functioning society. But during political transitions, such as changes in government or war, more reconciliatory approaches may be more suitable. Dr Cheah doesn’t use a lot of legal jargon, but she teaches us the legal concepts that are important,” he said.

Dr Cheah with her students from her Transitional Justice class in AY2014/2015 Semester 2

Today’s Pressure on CV-Building

Dr Cheah notices that students go for internships that are as short as two to three weeks during the holidays. Concerned, she expressed that we often underestimate how much time we need to learn new skills and complete tasks in a meticulous and responsible way.

“Being detail-oriented and meticulous is an underrated skill. In pro bono cases, it’s not about how many cases you completed, but about giving each case your best, ensuring that you have pursued every single lead and given the applicant the best benefit of the doubt. Learning how to compile that file (to be shown to the lawyer) – including every detail, ensuring that your claim is put forward in the best possible manner, choosing the correct words – takes time.”

“Even when doing mind-numbing things, such as transferring numbers from a file to an Excel sheet, or summarising information into an Excel sheet, you learn to be detail-oriented and accurate. But students tend to ask for another task, or put in less effort,” she continued. She believes carelessness reflects poorly in all professions, as when she wrote the wrong date when sending out a document to a member state when she was working at the Interpol.

She encourages students to invest in longer internships, to forge relationships and learn perseverance. Dr Cheah stressed the importance of resilience. “For every internship I got, I probably sent out 25 applications.”

Dr Cheah at a sharing session on 'Careers in Public International Law' organised by the Women in International Law - Singapore (WIL.S) (15 October 2015). The WIL.S has launched a mentorship programme to connect female students and early career lawyers with experienced women working in public international law.

I am grateful to have the chance to speak with Dr Cheah and share with you what I learnt of, and from her. Hopefully, reading this piece will give you some food for thought, be it about service to the public, your awareness of inequality and injustice, or your outlook and means towards chasing your dreams. For those who have not taken Dr Cheah’s module, do look out for it when it is next offered in USP.