Meet Our Writer-in-Residence Miriam Bird Greenberg: A Poet, Traveller and Anthropologist

By Stacy Ooi (Sociology + USP, Class of 2018)

Stacy is a student writer for USP Highlights.

Published: 29 August 2017

On 18 August Friday, I had the honour of interviewing Miriam Bird Greenberg, a visiting poet from Texas, America. Ms Greenberg has been selected as a Writer-in-Residence for the 2017 Singapore Creative Writing Residency, an annual programme jointly organised by the University Scholars Programme (USP), the NUS Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS), and The Arts House. The programme has been established since 2011, and offers up to two residencies each year: one to a local writer, and one to an international writer. Past Writers-in-Residence under this programme include Faith Ng (playwright at Checkpoint Theatre) and Dan Koh (co-founder of POSKOD.SG).

I met Ms Greenberg for our interview at the Cinnamon College (USP) where she will be living and interacting with students this semester. Sitting ourselves comfortably in the common student lounge on the ground floor, I asked her about her work, the influences that inform her poetry, and the poetry workshops that she will be running for USP students.

Although Ms Greenberg is a poet by trade, her interests are wide and far-ranging, expanding to include history, sociology, anthropology, hitchhiking, travel, train-hopping, and many more. “So much of what I'm interested in is not poetry,” she explains, “But I use poetry as a means of facilitating it.” Currently, she is working on a fieldwork-derived manuscript based on the Chungking Mansions in Hong Kong, and aims to capture the diversity of stories of the many migrants who live and work there - Indians, Africans, Pakistanis, Nepalese, Chinese, Hong Kongers, and many more.

In line with the interdisciplinary ethos of USP, she brings many methods to bear upon the project of poetry--she conducts informal interviews with people she describes as "on the margins" of mainstream society, she reads up on anthropological methods of doing research, and she seeks to develop an ethical system regarding how to sensitively depict the stories of other people. A great deal of her work can be described as what she calls "documentary poetry", and this genre will figure prominently in the workshops she plans to run for USP.

Motivation behind her poetry works

Her most recent poetry collection, "In The Volcano's Mouth", was published in 2016 to critical acclaim. Drawing on the years she spent hitchhiking and train-hopping, when she was in her 20s and early 30s, she wrote this collection of poems with the aim of capturing the people, lives and stories she came across on the road. Many of the travellers she met wanted a life outside of mainstream society. Particularly memorable to her was an off-the-grid community called “Slab City”, located in the desert, about three hours east of LA, Southern California. Slab City was filled with artists, hitchhikers, hangers-on, bikers, and even a large, established community of widowed RVers who spent their winters in the Slabs. The inhabitants of Slab City came from a huge diversity of social and class backgrounds, but what many of them had in common was that they had chosen to opt out of mainstream society for a great variety of reasons.

Many of the inhabitants had also fallen through the social safety net of American society in some way. America, Ms Greenberg explains, does not have Singapore’s equivalent of subsidised housing or subsidised healthcare. “It often means that if your family is not wealthy, and/or you haven't had a good job that comes with a pension, you may not have any idea of what you're going to do when you retire. And so, a lot of the people who settle in the Slabs are people who wouldn't have much of a social safety net, but they found this sort of other family [in the Slabs].”

Several of the core poems of "In The Volcano's Mouth" (2016) came from time she spent at East Jesus, a small community of artists located within the larger, loose community of the Slabs. East Jesus exists on the edge of the Slabs, and differs from mainstream American society not just materially, but also socially and politically. In terms of the physical conditions of survival, “electricity is difficult, water is difficult, finding cool in the heat is difficult, and so to survive in the Slabs, either requires a lot of ingenuity, or a community that helps one another.” In terms of the political and social structure of the community, East Jesus inhabitants make conscious decisions not to reproduce the dominant power structures of American society. The people there have “actual conversations” about what they want the social norms of their community to be, not necessarily in an academic or scholarly way, but nonetheless asking questions about “what do we want, what do we want this world to be like, [and] who do we want to feel welcome here”. She explains that “if there's somebody around who doesn't respect women, or who is homophobic - those people are asked to leave”.

As a traveller-poet, Ms Greenberg has inhabited many different worlds apart from the Slabs. She grew up in rural Texas, on a farm that had been owned by her mother’s family for almost two hundred years, such that she was surrounded by echoes of history even as she grew up in modern America. “As a kid I tried on the dresses that my ancestors a hundred years ago wore, and the house was full of layers of history - the bed I slept in, the furniture in the house, the dishes that we used, the farm implements that we used… It was this pastiche of a hundred years old, eighty years old, and [things that] we bought yesterday…”

The strong sense of other worlds, of other times and places other than her own, permeates much of her writing. Whether she is inventing new worlds and dystopias, or documenting the way other people create their own universes of meaning, she is strongly interested in the “world-making impulse” that is innate to all human beings, and how she as a writer can navigate the multiple realities in this world. A chameleon-like nature, facilitated by the skills of empathy and imagination, is necessary for any writer-traveller to truly appreciate the different environments that they find themselves in. When I asked her how she reconciled her identity as an explorer of various non-establishment communities around the world, with her current status as Writer-in-Residence of a very established university in Southeast Asia, she responded with a laugh, “Well, I probably have five different answers to this. One of which would say... I don't really feel at home anywhere. And the other of which would probably be the total opposite.”

Having travelled and hitchhiked extensively, she finds that the ability to code-switch is invaluable to her vocation as a writer. “One of the most important skills that a writer shoulddevelop, as part of their training, is the ability to kind of code-switch, to move between places, contexts, [and] social milieus.” She adds that feeling like an outsider or foreigner is often a necessary part of the anthropological and literary process. Writers who wish to document worlds beyond their own may not necessarily feel “at home” or “comfortable”, but their task is to “push through that discomfort long enough to see the complexity that makes that place, context or situation so much richer and more nuanced than [one could] understand as an outsider”. As a writer-traveller who feels comfortable with discomfort, then, switching between the radical ethos of a community like East Jesus and the decidedly-less-radical philosophy of the National University of Singapore is just part of the process for her.

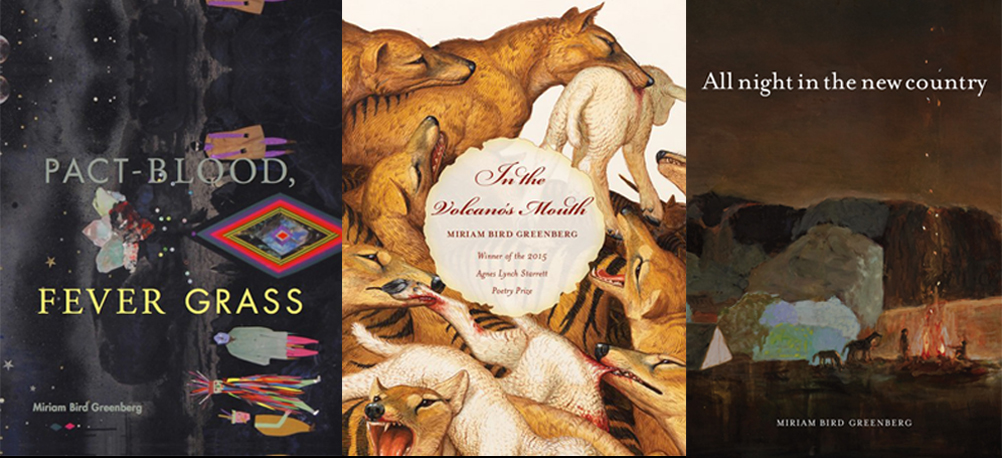

Some of Miriam's book collection

Her current literary work

Her current work on the Chungking Mansions in Hong Kong is especially demanding in terms of the amount of code-switching it requires from her. “Writing about a place like the Chungking Mansions which is just so dense and rich and varied… it’s important to do it well, right,” she says. Drawing loosely on the words of anthropologist Gordon Mathews who teaches at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, she describes the Chungking Mansions as an "intercultural nexus of the low-end global economy", where economic migrants and asylum seekers from Asia and Africa end up trying to carve out a life, sometimes without even having intended to end up in Hong Kong.

The diversity of the Chungking Mansions makes it an interesting test of the human ability to adapt and work together. In such an environment, mistrust and racism inevitably crop up. She laughs as she recounts how “depending on who you talk to, you'll hear people say - you can't trust ‘fill in the blank’. And so I can have a few conversations over the course of the day and learn that you can't trust Indians, can't trust Pakistanis, can't trust Nepalese, can't trust people from West Africa, can't trust people from East Africa…” That being said, she also emphasises the unlikely friendships that emerge, and the fact that many people do get along quite warmly despite their cultural differences. She observes that many unlikely alliances form amongst the people of Chungking Mansions: “So you see for example, Muslim shopkeepers and their Hindu shop assistants, mainlanders and Hong Kongers working together, or you'll see Africans doing business with Indians, or all of these unlikely alliances.”

She seeks to portray the stories of these economic migrants in a way that “honours” rather than merely romanticises them. She is exploring how she, as an outsider, can ethically represent people whose experiences are “poorly understood” by mainstream society. Ultimately, to ensure the integrity and accuracy of her project, she plans to show her poetry and documentary work to the people she’s written about in the Chungking Mansions - “I'll make an effort to make sure that they have them,” she says firmly, “And [I’ll ask] - what do you think of this? Did I get this right in some situations?”

The value and purpose of poetic and literary thinking

Ms Greenberg uses poetry as a way of documenting these experiences, drawing on literary thinking to make sense of places such as the Chungking Mansions, outsider communities in the US, rural Texas, and the world in general. This raises two questions: firstly, why use poetry to study field sites more commonly studied through the lens of the social sciences? Secondly, why engage with field sites at all, when there is no strict necessity for poets to incorporate empirical or anthropological research into their work?

The first question invites us to consider the value of poetic and literary thinking. Ms Greenberg is firm in her conviction that poetry provides an alternative way of “knowing”, and that it is valuable to look at places through a literary perspective, rather than just using quantitative or qualitative lenses. Although the social sciences may be able to nail down “specific detail”, poetic knowledge is more able to provide a holistic understanding of “time, place, milieu or zeitgeist”. She describes the latter as “these things that build the world, but don’t quantify it”. The innate structure of poetry, which allows the poet to move through or around ideas with a great deal of flexibility, and which allows the poet to move away from a single unified speaker into a “disunified multi-vocal approach”, is also what she considers to be one of the unique abilities of poetry as a genre.

The second question makes us reflect on the many different “purposes” that poetry can be called upon to serve. Ms Greenberg observes that there are many types of poetry. Some people use poetry as catharsis for their emotions, using it to heal from heartbreak or loss or grief. Some people use poetry to heighten the moments of ordinary life and enable the “transcendence from ordinary life to the spiritual”, bringing it out for example to celebrate a wedding, or mark a funeral. Yet she feels that it is limiting to think of poetry only as a means of accessing the sacred, or only as a means of catharsis. She uses her poetry to document this world, without necessarily aiming to transcend it, because she feels that there is value in using poetic knowledge to make sense of current global patterns such as economic migration, race, nationalism, and so on. Hence she seeks to connect her poetry to some kind of empirical grounding, and seeks to give her poems a historical context.

Her workshops at USP

Through the workshops she will be holding for USP, Ms Greenberg will teach students how to use poetry to make sense of the world, and guide students to work on assignments that are documentary or fieldwork informed. Although poetry can be a highly solitary activity, the “workshop model” of teaching poetry brings a social element to the process, and helps students become aware of how their work comes across to an audience. The “workshop model” is a model of critique often used for teaching the arts within an academic context, and is something that Ms Greenberg has been familiar with for a long time--she has been in workshops for half her life, ranging from informal workshops in high school, to more formalised workshops in graduate school.

She describes the “workshop model” as a warm, welcoming and generous space where writers come together to critique each other’s work, and be critiqued in return. Everybody should ideally bring a poem each week, to demonstrate that they have “skin in the game” and are willing to risk a little vulnerability. Through workshops, Ms Greenberg explains, writers learn about the “mutual support and mutual responsibility” necessary to keep a healthy feedback cycle going. They learn how to give feedback that is not just rigorous, but also well-suited to the project that each individual person brings. For instance, the critique that one person’s work would benefit from might differ vastly from the critique another person might need to hear, and the critique that would be valuable to a beginner would differ from what a more experienced poet would require. One important aspect of criticism is therefore to “meet the poet where s/hes at”, and be conscientious of tailoring one’s feedback to the specific project or goals or interests of the writer. This requires a certain amount of self-discipline, as writers critiquing their friends’ work must be aware that what they “like” or “dislike” in a poem is not necessarily the same as what “works” or “doesn’t work”. The larger goal of critique is not simply to say “I love this poem”, but to go beyond personal taste and answer bigger questions - “You love it, but what makes it so good? Is it just [that] you like this image? Or does the image connect to something broader in the poem, or in society?”

Ultimately, Ms Greenberg hopes to provide an introduction to the workshop model, for people who have not encountered it before, as well as an introduction to poetry, for those interested in learning how poetry offers an alternative form of knowing. She remarks that people often do things in poetry with the help of their unconscious mind that they could never have plotted out with their conscious mind. We look forward to the valuable contributions that Ms Greenberg will bring to the USP community, as she helps us explore the depths of our imagination and unconscious.

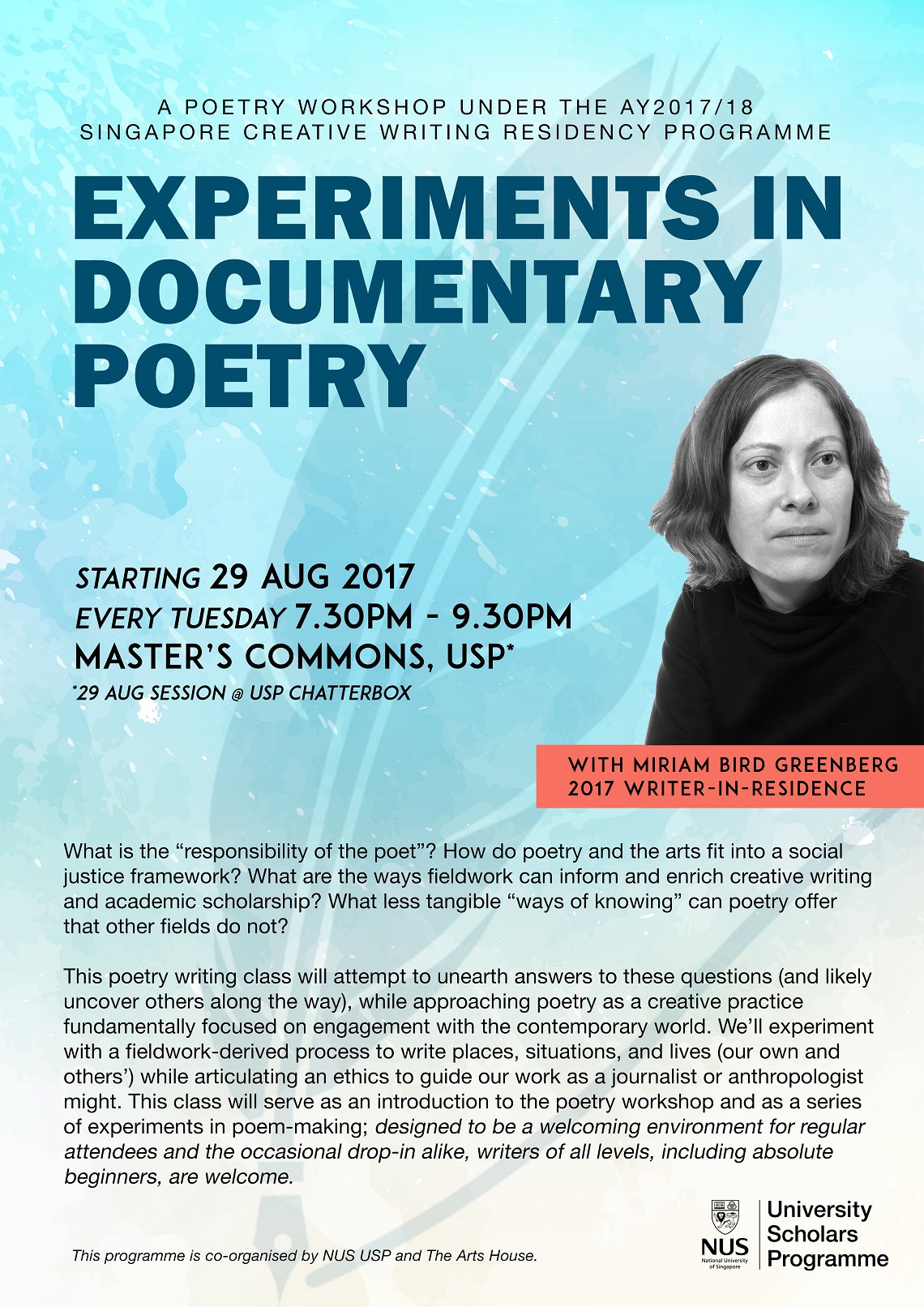

Miriam Bird Greenberg, Writer-in-Residence for the 2017 Singapore Creative Writing Residency, will be holding a series of workshops for USP students in AY 2017/18 Semester 1. The first workshop, Experiments in Documentary Poetry, will be held on Tuesday, 29 August 2017, 7:30-9:30pm at USP Chatterbox. Subsequently, the workshop will be held on Tuesday nights at USP Master's Commons.

More about her

She is the author, most recently, of In the Volcano's Mouth, which won the 2015 Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize from the University of Pittsburgh Press and was released in October 2016. She has been recognised with fellowships from the NEA, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, and the Poetry Foundation. The author of two previous chapbooks—All night in the new country (Sixteen Rivers) and Pact-Blood, Fevergrass (Ricochet Editions)—her works have appeared in Poetry, The Missouri Review, Zyzzyva, Lambda Literary Spotlight, Sycamore Review, and the anthologies Best New Poets 2014 (Samovar) and The Queer South (Sibling Rivalry). A former Wallace Stegner Fellow, she lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, where for many years she collaboratively developed site-specific performances for very small audiences.

The daughter of a New York Jew and a goat-raising anthropologist involved in the back-to-the-land movement, Miriam grew up on an organic farm in rural Texas. She teaches creative writing and ESL, though she’s also crossed the continent aboard freight trains and as a hitchhiker, plus bicycled a few thousand miles in the US, Canada, Thailand, Burma, and China. Supported by a grant from the John Anson Kittredge Fund, she's working on a fieldwork-derived manuscript centered on the economic migrants and asylum seekers of Hong Kong’s Chungking Mansions.

Read Miriam Greenberg's works here.